Reconstructed Room Block at Lost City Museum, Overton, Nevada

The title of this blog comes from the Navajo legend about Chaco Canyon, recorded in several forms, which describes it as the home of the Great Gambler, a stranger who came to the Anasazi and managed to enslave them by gambling with them and winning until they had nothing left to bet but themselves. As the story goes, the Gambler forced his new slaves to construct the great houses of the canyon, including one in particular where he himself lived. Most versions of the story identify Pueblo Alto as this house, which is odd and intriguing since it is today one of the least remarkable or impressive of the major great houses, and the banner image on the blog is therefore cropped from a picture I took of Pueblo Alto.

Beyond that specific context, however, I’ve found that the theme of gambling runs continually through my thinking on Chaco and what lessons it holds for our society today. In one sense, building the great houses of Chaco at all in its harsh and unpredictable environment can be seen as a gigantic bet on continued favorable climatic conditions, and ultimately and unsuccessful one. And, as we are now finding to our increasing discomfort, many of the more impressive works of our own society are based on similar bets, and the odds are beginning to look a lot longer than they did before.

I’m writing this in Las Vegas, Nevada. This is a city famously devoted to gambling in all its forms, and it’s also one of the most obvious examples of the large-scale gambling on environmental conditions which has in some ways been the halmark of modern America. While I’ve been here I’ve looked at a lot of the city, including many parts that visitors don’t usually see, and what has struck me most is that it really seems like a city on the edge, not only environmentally but economically as well. This is one of those places that invested heavily in the housing boom and is suffering correspondingly from the housing collapse, and there are signs and ads all over town offering sales of various sorts and directly referencing the recession. The same is true of ads I’ve heard on the local radio stations. This has been a pretty prosperous place for a long time, but now it seems like the possibility of it turning into an enormous slum is looming ominously on the horizon. Not that that will necessarily happen, of course; it’s never wise to try to predict the future. But the potential is clearly there. The past success of a given bet is no guarantee of continued success.

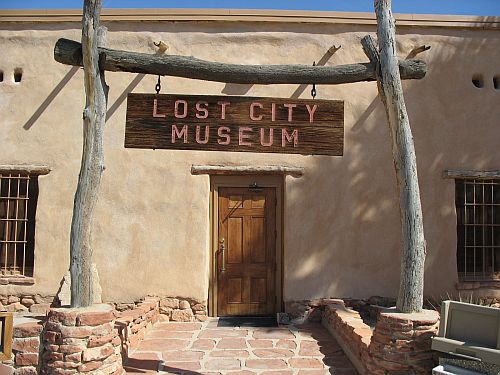

Lost City Museum, Overton, Nevada

This isn’t the first time people have made bets like this in what is now southern Nevada. Just before I came here I visited the Lost City Museum in Overton, Nevada, which was constructed to house the artifacts from the salvage excavations of sites threatened by the creation of Lake Mead. The name “Lost City” was given to the extensive series of ruins in the Moapa Valley by early promoters in the towns established there in the late nineteenth century, and for several decades they were a major tourist attraction for places like Overton and, especially, St. Thomas, further downstream, which itself became a lost city when it was inundated by the lake and has now reappeared as the waters have receded in response to severe drought.

The ruins, also known as “Pueblo Grande de Nevada,” were from the Virgin Anasazi culture, which flourished here for a long time and was partly contemporaneous with the rise and fluorescence of Chaco far to the east. There is no clear evidence of contact between the people here and those of Chaco, but there are some interesting parallels in their development, including extensive regional trade networks and the import of considerable amounts of basic goods like pottery. Although the system here was on a much smaller scale than that of the cultures to the east, it was still pretty impressive given the extreme harshness of the local environment.

It’s generally agreed that the Pueblo II period, roughly AD 900 through 1100, the time of the greatest extent of both Chaco and the Virgin branch, was a time of unusually favorable climate in most of the southwest, and that this had some relationship to the spread of the Pueblo cultural tradition to its greatest extent at this time. Around AD 1100, however, the climate seems to have deteriorated remarkably for a long time, culminating in the “Great Drought” of the late thirteenth century, and the fact that the prehistoric cultures of the southwest underwent many considerable changes at this time is often thought to be related to that deterioration.

Among the changes at this time, beginning somewhat earlier than some of the others, was the disappearance of the Virgin branch. This, in other words, was when Lost City was lost. After AD 1160 or so, Pueblo occupation of the area seems to have ceased entirely.

Original Foundations of a Room Block at Lost City Museum, Overton, Nevada

Why Lost City was lost is in some respects clear, given the environmental difficulties at the time, but in other respects a bit murky, given that the timing is somewhat out of sync with the rest of the region. In any case, there is an abiding mystery remaining, and that is what happened to the people.

In most of the southwest, although the details are not always clear, the overall answer to what happened to the people when they left sites that are no longer occupied is pretty clear: they went to the areas that are still occupied by their descendents, namely the Rio Grande Valley and the Western Pueblo areas, including Hopi, Zuni, and Acoma-Laguna. In fact, we spend a certain amount of time at Chaco disabusing visitors of the “vanishing Anasazi” idea. The Chacoans didn’t vanish. They moved.

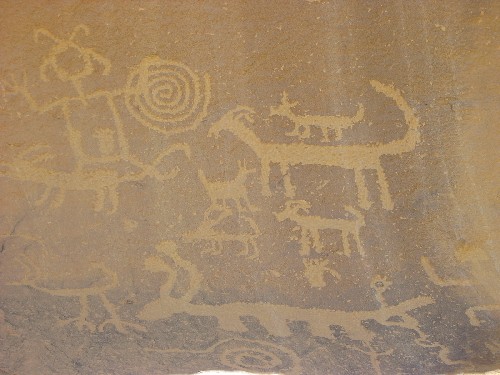

Abstract Petroglyph Panel at Valley of Fire State Park, Nevada

The Virgin Anasazi, however, did vanish. Or, at least, there is no clear evidence of them moving anywhere else. While the Virgin area was abandoned earlier than most others, it is not possible to trace a wave of movement to the east into the areas still occupied at the time, such as the Kayenta, Mesa Verde, and Hopi regions. If the Virgin people emigrated en masse, presumably some trace of their movements should remain, either in the demographics of nearby areas or in artifacts showing a similar material culture showing up in those areas. There is, however, no such evidence. If the Virgin Anasazi moved to other regions, they did so in small groups and assimilated completely to the culture of the areas they went to. This is of course totally possible, and the Hopi, at least, consider the Virgin people among their ancestors, but not all archaeologists accept it, given the paucity of positive evidence.

But if the Virgin Anasazi didn’t emigrate, what happened to them? One possibility is that they drastically changed their material culture to adapt to the changing climate and became the hunting-and-gathering Southern Paiutes who inhabited the region at European contact. This is in fact the account preferred by the Southern Paiutes themselves, who consider the Virgin Anasazi their ancestors, but Paiute material culture is so different from that of the Anasazi that most archaeologists are skeptical and are willing to accept at most that the Virgin branch assimiliated (again, completely) to the culture of the Paiutes, who they see as entering the region as the climate changed.

The only other option, which many archaeologists seem to prefer, is that the Virgin Anasazi, who were never very numerous, died out entirely as they conditions. I’m a bit dubious of this given the considerable flexibility shown by Pueblo groups further east, but I’m no expert on this area, which is in some ways even more difficult to live in than the Colorado Plateau.

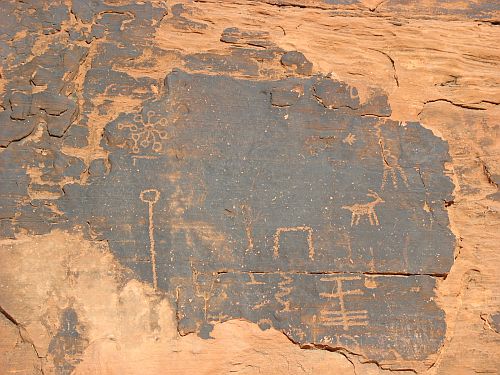

Abstract Petroglyph Panel at Atlatl Rock, Valley of Fire State Park, Nevada

In any case, what is clear is that the bet made by the inhabitants of Lost City was ultimately unsuccessful. It is unclear how they responded to this loss, but given that we seem to be in a similar situation in the same area, I think more study of the issue is crucially important.

Somewhere the dice are rolling. The result is, as always, uncertain, but the odds are long. There are already two lost cities in southern Nevada: Pueblo Grande and St. Thomas. Will Las Vegas become the third?

Reconstructed Ceiling Hatch at Lost City Museum, Overton, Nevada