Visitor Center and Fajada Butte from Una Vida

Chapter five of Crucible of Pueblos brings us to Chaco Canyon and the surrounding area. This is an area of particular interest for me, and I presume for most readers of this blog as well. While the rise of Chaco in the tenth and early eleventh centuries AD was clearly a development rooted in earlier events, there has long been less information available for the area of Chaco itself than for the areas to the north that have seen extensive relatively recent excavations of sites dating to the Pueblo I period. The Pueblo I occupations of those areas, the subjects of the earlier chapters in this book, are now fairly well understood, although there of course remain a lot of questions and gaps to fill. Further south the picture is still much murkier.

This chapter is written by prominent Chaco specialists Tom Windes and Ruth Van Dyke, and is particularly important and useful because it includes the first published synthesis of the work Windes has been doing for many years to identify sites in and around Chaco dating to the Pueblo I period. This work was written up as part of the series of reports on the work of the Chaco Project, but that report, dated 2006, remains unpublished. I presume that this is a deliberate decision on the part of the National Park Service to keep sensitive information on site locations from becoming public (although I don’t actually know for sure). This chapter, then, appears to serve as the published record of this important work, which significantly alters the conventional interpretation of Pueblo I in Chaco.

The authors define their geographic scope as what they call the “Chaco Basin,” which is essentially equivalent to what is commonly know in the Chaco literature as the “San Juan Basin.” I think this is a useful change to the terminology, since “San Juan Basin” in the hydrographic sense refers to a much larger area than it is used for in this context, and while some use terms like “San Juan Physiographic Basin” to clarify this, it’s more straightforward to redefine the area and use a new term. “Chaco Basin” is a good term to use because the area more or less corresponds to the drainage basin of the Chaco River, including its tributaries, although it extends a bit beyond to the east and south into the Puerco Valley and Red Mesa Valley respectively. However it’s labeled, this region is roughly bounded by the San Juan River to the north, the Chuska Mountains to the west, the Zuni Mountains to the south, and the Jemez Mountains to the east.

Temporally, the authors restrict their attention in this chapter to the period from AD 700 to 925, unlike some other authors in this volume who also address the preceding Basketmaker III period. This is understandable but in some ways unfortunate, since there was an important Basketmaker III occupation of Chaco Canyon that was likely important in setting the context for Pueblo I developments, just as those developments were important in setting the context for Pueblo II. Confusingly, they use the term “Pueblo I” for sites dating from AD 700 to 875 and “late Pueblo I” for sites dating from AD 875 to 925. As we’ll see below, the distinction between these two periods is important in this region, as population and settlement patterns changed significantly at around AD 875. The specific terms they use still seem odd and liable to cause confusion, however.

Part of the reason the authors argue that the Pueblo I occupation in this region is poorly understood is that the ceramic chronology is different from that of the better-known sites to the north, and using the same types to identify time periods for sites in both regions leads to problems. They carefully define the types they use to identify sites to time period, and also use architectural criteria (which are however difficult to apply to unexcavated sites).

Most of this chapter is a summary of what is known about Pueblo I settlement in each subregion of the Chaco Basin, based in large part on hitherto unpublished fieldwork. As a result, I will structure this post according to the same subregions in the same order and summarize the information on each.

Northern and Northeastern Areas

The heading for this section says “Northwestern” rather than “Northeastern,” but it’s clear from the text that this in error. These areas, north and northeast of the Chaco River but still within the drainage of the San Juan, were sparsely populated throughout the Pueblo period. Windes and Van Dyke note that the Largo and Gobernador canyons, to the northeast of Chaco, may have served as conduits for populations migrating south from the Mesa Verde region into the Chaco Basin in late Pueblo I. A recently discovered village at the confluence of Largo and Blanco Washes included a great kiva and at least 22 habitation sites, with tree-ring dates from the great kiva pointing to construction at about AD 828. This area is roughly due south of the Cedar Hill and Ridges Basin areas of the Animas Valley, considered part of the Eastern Mesa Verde region in this volume, which had extensive but short-lived populations early in Pueblo I. The tree-ring dates from the Largo-Blanco village suggest that it may have been associated with the initial migration out of the Ridges Basin/Durango area in the early 800s rather than the larger migration in the late 800s. The Chaco River may have been another conduit for migrants from the north, as Windes and Van Dyke note that surveys have found a major increase in sites dating to the late 800s along the east side of the Chaco, compared to a virtual absense of sites for earlier in Pueblo I. This will be a recurring pattern in the region.

Chaco Canyon Proper and Environs

The initial survey work of the Chaco Project in the 1970s identified a fairly extensive Pueblo I occupation in and around the canyon, and publications from that time posited a gradual increase in population over the course of Pueblo I leading up to the florescence of Chaco as a regional center in Pueblo II. Based on his more recent work with ceramic classification and dating, however, Windes disputes this account. He argues that the number of sites assigned to Pueblo I in those surveys is vastly inflated, and that for most of the Pueblo I period the Chaco area had a small population which increased dramatically, presumably due largely to immigration, in the late Pueblo I period. In this chapter Windes and Van Dyke (though clearly this part is mostly Windes) summarize the results of Windes’s reevaluations of the Pueblo I occupation in and around the canyon, moving from east to west.

Pueblo Pintado Great House at Sunset

At the east end of Chaco Canyon, the Pueblo Pintado area was apparently unoccupied until about AD 875, when it was colonized by two groups who had markedly different material culture and appear to have come to the canyon from different directions. They formed separate site clusters about 3 km apart, north and west of the later great house of Pueblo Pintado.

The first cluster, located just north of the great house, includes one exceptionally large roomblock more than 50 meters long, accompanied by a trash midden that is also unusually large. Based on the temper of early ceramics in this cluster, the people appear to have come from the Mesa Verde region to the north, presumably as part of the mass exodus following the collapse of the Dolores villages in the late ninth century.

The second cluster, 3 km west of the first one, appears to have also been founded around AD 875 but continued in use well into the Pueblo II period. The ceramics are quite unusual in manufacture for the Chaco area and indicate origins to the south in the Mt. Taylor area. Interestingly, the roomblocks in this cluster were aligned along the road connecting the Pueblo Pintado community to the core area of Chaco Canyon, implying that this road may date to the late Pueblo I period.

Moving west, the next major cluster of Pueblo I sites is what is known as the Chaco East community, which also featured a later great house. This area also appears to have been unoccupied until about AD 875, when it was colonized by a group occupying small residential sites, possibly only seasonally. In the 900s the community grew considerably, and initial construction of the great house may date to this period, although it’s impossible to tell for sure without excavation.

Third-Story Walls with Type I Masonry at Una Vida

Fajada Gap, at the eastern end of the main concentration of sites in Chaco during Pueblo II, is one of the areas where early surveys indicated a dense Pueblo I occupation which Windes disputes based on current understandings of the ceramic chronology. In fact, while there was unquestionably a small occupation of the area throughout Pueblo I involving scattered hamlets, this appears to be yet another part of the canyon where there was an influx of people in the late 800s who established the basis for the community that developed subsequently. There are two great houses in this community, Una Vida and Kin Nahasbas, both of which were constructed beginning in the late ninth century.

The largest Pueblo I (pre-875) settlement in the Chaco area is actually outside the canyon, along the South Fork of the Fajada Wash. This community contained 26 sites in an arc along the west side of the South Fork; no contemporary sites are present on the east side. The community is loosely clustered around a complex of four roomblocks which were connected by a short road to a great kiva, and it likely included about 230 people overall. Its main occupation was around AD 800, making it contemporary with the earlier villages in the Mesa Verde region, but the layout of the community is more like later villages such as those at Cedar Hill and in the Largo drainage. (The description of the community in this chapter is very confusing and it’s hard to tell in what respects it’s being described as similar to or different from villages in other regions.)

Many of the potsherds from the South Fork community were tempered with chalcedonic sandstone, which is typical of sites to the south near the modern community of Thoreau. There is also an unusually high abundance of yellow-spotted chert among the chipped stone assemblage, again indicating connections to the south. This type of chert occurs in the Zuni Mountains near Thoreau and is common in sites in that area.

Although this was the largest Pueblo I community in the Chaco area, it appears to have been very short-lived, with little trash accumulation. This suggests that the Pueblo I period was a dynamic time of extensive population movements in this area just as it was in the better-understood areas to the north. The subsequent Pueblo II occupation of the South Fork was much more extensive than the Pueblo I occupation and quite different, with sites dispersed up and down the valley rather than clustered in one area. A similar though somewhat smaller cluster of sites dating to the Pueblo I period was also present in the upper reaches of Kin Klizhin Wash to the west of Fajada Wash.

Old Bonito

Returning to the main canyon, there were a few scattered Pueblo I hamlets between Fajada Gap and South Gap, but the occupation doesn’t seem to have been extensive. Even in South Gap itself, an area of considerable density during Pueblo II and the location of the cluster of great houses known as “Downtown Chaco,” Pueblo I occupation was sparse, with a few scattered sites in the gap. Apparently the only Pueblo I site known in this part of the canyon proper is Pueblo Bonito, where the earliest construction of the great house, known as “Old Bonito,” dates to the mid-800s (or possibly even earlier) and there is also an earlier pit structure excavated by Neil Judd in the 1920s. Judd thought the pit structure reflected an earlier occupation unrelated to the great house, but with improved dating showing that the great house was begun earlier than had been thought the idea of continuity is beginning to seem more likely.

There is no evidence for Pueblo I occupation between South Gap and the mouth of the canyon, possibly on account of flooding creating an intermittent lake on the canyon floor. At the mouth of the canyon itself, the Peñasco Blanco great house, begun in the late 800s, sits atop West Mesa, and right next to it is the important Basketmaker III village of 29SJ423. The period between these two important occupations, however, appears to have involved only minor settlement, although there are a few scattered Pueblo I sites. Just west of the mouth of the canyon, however, is Padilla Wash, which had a substantial Pueblo I occupation (possibly even more extensive than current records indicate, since many Pueblo I sites may have been misclassified as Basketmaker III in earlier surveys), another example of the main centers of Pueblo I population in the Chaco core being outside the canyon proper. Windes and Van Dyke note that Peñasco Blanco may have been an important focal point for migration into the canyon from the west and north during late Pueblo I, and that it was likely more important than Pueblo Bonito at this time.

The Chaco River

As noted above, the Chaco River (formed by the confluence of the Chaco and Escavada Washes at the mouth of Chaco Canyon) was likely one of the main conduits for migrants from the north, but it was much more than that. Pueblo I communities existed all along the Chaco and its tributaries, and some of these communities included early great houses that would have been influential in the development of the great house phenomenon that found its greatest expression in Chaco Canyon in the eleventh century. Windes and Van Dyke discuss a number of these communities, based on field research by Windes to reevaluate areas identified by early surveys as Chacoan outlier communities and to look for evidence of Pueblo I settlement and early great houses.

Just west of Padilla Wash is Kin Klizhin Wash, which was the site of extensive Pueblo II occupation but only has a few Pueblo I sites aside from the cluster at its upper reaches mentioned above. There is a late Pueblo I great kiva known as Casa Patricio in the upper part of the drainage, accompanied by a number of late Pueblo I residential sites; it’s not clear from the writeup here what relationship this site cluster has to the earlier Pueblo I cluster.

Just downstream from the mouth of Kin Klizhin Wash is the very important early site known as Casa del Rio. While this was initially labeled a large Chacoan great house, reexamination indicated that it is actually a composite of two building stages, both relatively early, with much of the bulk of the structure provided by a Pueblo I roomblock measuring 112 meters in length, with a later masonry great house built over the central portion beginning in the late ninth century. The early roomblock is by far the largest in the Chaco Canyon region, more than twice the length of the earliest construction stage at Pueblo Bonito, and it is estimated to have housed about 16 households or 88 residents. Windes and Van Dyke describe it as “reminiscent of those north of the San Juan River,” although again it is not clear what specific characteristics this refers to. A large number of food preparation tools were found in the area, although other residential sites are scarce. This was clearly an important site during the Pueblo I period which may have played a key role in attracting migrants to the area.

Looking North from Kin Bineola

One of the most important tributary drainages of the Chaco River is Kim-me-ni-oli Wash, which extends from the Dutton Plateau north past the current site of Crownpoint. The drainage of this wash includes several great houses and extensive Pueblo settlement, and it likely served as an important conduit between Chaco Canyon and areas to the south and southwest. The extent of Pueblo I occupation, however, seems to be unclear. Windes and Van Dyke mention large circular structures near the Bee Burrow great house that resemble Pueblo I great kivas, as well as small Pueblo I roomblocks in the same general area. The area around the Kin Ya’a great house at the upper end of the drainage appears to not have any Pueblo I occupation based on existing survey data, although there is a large Basketmaker III-Pueblo I site just west of Crownpoint and one arc-shaped roomblock near Kin Ya’a recorded as dating to Basketmaker III looks a lot more like a Pueblo I site. At Kin Bineola, site of a major great house dating to the early 900s or possibly slightlier earlier, there is a very small Pueblo I occupation that increased substantially after AD 875 as in many other parts of the region.

At the mouth of the Kim-me-ni-oli Wash near the current Lake Valley Mission there is a small cluster of Pueblo I sites “architecturally identical” to the South Fork cluster, with very sparse refuse indicating a very short occupation. A later occupation in the late 800s was more substantial, with three masonry roomblocks “sometimes portrayed as small great houses” and “enormous amounts of refuse” that Windes and Van Dyke describe as “excessive for normal domestic activities.”

Further down the Chaco drainage, the Willow Canyon area is unusual in showing evidence of both middle and late Pueblo I occupation in close proximity. The middle Pueblo I community consists of eight sites that show the typical “scattered hamlet” settlement pattern, while the eleven late Pueblo I sites are tightly clustered and associated with a large amount of refuse, leading the authors to interpret this as “a large group” that immigrated into the valley together. These sites show unusual amounts of Type I masonry, associated with later great house construction, although the authors declare that there is no “obvious” great house. It’s not clear what definition of “great house” they are using here, as one site in particular (known as the “House of the Weaver”) shows not only Type I masonry but a prominent mesa-top location with a broad view of the surrounding area, another common characteristic of later great houses. Another community south of Willow Canyon near the later Whirlwind great house also shows a similar pattern but has less information available. The Great Bend area, where the Chaco River turns from flowing west to flowing north toward the San Juan, also shows this pattern. The possible use of the river as a corridor for populations migrating from the north after the collapse of the Dolores villages makes this potentially an important area for understanding regional prehistory.

Chuska Mountains and Chaco River from Peñasco Blanco

The eastern flanks of the Chuska Mountains, which parallel the north-flowing segment of the Chaco River and form the western side of its drainage basin, are also important for understanding Pueblo I settlement but are poorly known. The general pattern seems to be the same as elsewhere in the Chaco Basin, with a scattered occupation in early and middle Pueblo I that sees a huge increase, presumably from immigration, in late Pueblo I after AD 875, but due to depositional factors it’s likely that the earlier Pueblo I occupation has been underestimated. A few sites dating to this period have been excavated through salvage projects. Late Pueblo I sites are more common and seem to provide more evidence for the use of the river as a corridor from the north. The largest concentrations are in the Skunk Springs and Newcomb areas, both of which would become major Chacoan outlier communities in Pueblo II. At Newcomb, at least, there seems to be some evidence of a preexisting Pueblo I occupation. It’s not clear if there is any similar evidence at Skunk Springs, where the earliest stage of construction on the great house seems to date to late Pueblo I. Given the importance of Chuskan imports to Chaco at its peak, more research on the background of these communities would be helpful in understanding Chaco’s origins.

The Red Mesa Valley

The Red Mesa Valley is the area between the Dutton Plateau on the north and the Zuni Mountains on the south. It is topographically rather than hydrologically defined, and straddles the Continental Divide, with the western part drained by the Rio Puerco of the West and the eastern part drained by the Rio San Jose. This means it falls outside of the “Chaco Basin” as hydrologically defined, of course, but its culture history means that it makes sense to include it with areas to the north for purposes of this chapter. This valley was presumably an important travel corridor prehistorically, as it certainly was historically with the railroad and Route 66 running through it and remains today with Interstate 40.

Casamero Pueblo

This area has been the main focus of Van Dyke’s research, and it is clear that she rather than Windes is responsible for most of this section of the chapter. The same issues of ceramic identification as in the Chaco Basin make understanding the Pueblo I sequence here difficult, but the same basic pattern appears to apply as further north. Early in Pueblo I there was a small, scattered occupation, exemplified by a site on the mesa above the later Chacoan outlier community of Casamero. This site consists of at least two arcs of surface rooms fronted by five to seven pit structures, and resembles White Mound Village further west along the Puerco, which was excavated by Harold Gladwin in the 1940s and dates to the late 700s and early 800s. Another site like this from the same period was excavated near Manuelito during the construction of I-40 in 1961.

This sparse population expanded immensely in late Pueblo, when many of the later Chacoan great house communities were founded. Some of the earliest great house construction in the region took place in these communities, which Van Dyke has elsewhere used to argue that great houses were not initially associated particularly with Chaco Canyon specifically. The huge increase in population at this time seems to indicate immigration, but this chapter doesn’t address the issue of where the people in this area might have come from. Given the similarities to the communities to the north in the Chaco Basin, that seems like an obvious point of origin (with earlier origins probably further north in the Mesa Verde region), but developments to the south are poorly understood and can’t be ruled out as important factors. As noted above, some of the immigrants to Chaco Canyon and its surrounding area appear to have come from the south rather than the north, and southern origins would presumably be even more likely for the Red Mesa Valley populations given their location. The fact that the influx here appears to happen at the same time as the northern one is an interesting complication, however.

The Eastern Chaco Basin

This area, stretching from the area south of Chaco Canyon across the Continental Divide to the Rio Puerco Valley of the East, shows very little evidence for Pueblo I occupation. Today this is a very sparsely populated area used mainly for cattle ranching, primarily on private land, so there has been little archaeological survey, but what survey has been done shows very little prehistoric occupation at all. Only two exceptions are noted by Windes and Van Dyke. One is a recently discovered Pueblo I community southeast of Mt. Taylor, about which little is known. Detailed information from the survey that identified this community is apparently not going to be released. It’s not clear from the brief writeup if this has anything to do with the fact that the survey was for proposed uranium mining.

The other exception is the Puerco Valley of the East, around the later Chacoan outlier of Guadalupe. Here, survey by Eastern New Mexico University in the 1970s identified a “modest but scattered” Pueblo I occupation, which increased substantially in late Pueblo I and Pueblo II, culminating in the Guadalupe community with its apparently close connections to Chaco Canyon. Windes and Van Dyke note that the Puerco may have served as an important conduit connecting the Chaco Basin to areas further east, although it remains poorly understood. The eastern associations of Chaco are poorly understood in general, and this appears to be the case as much for Pueblo I as for Pueblo II.

Storm in the Distance through Fajada Gap

After going through the detailed geographical summaries, the authors briefly address some region-wide issues important for understanding the patterns they describe. They acknowledge environmental factors as probably important in understanding population shifts, pointing in particular to an apparent “spike” in rainfall in the immediate area of Chaco Canyon between AD 885 and 905 that might have served as a “pull” factor bringing people in from other areas. Conditions in the Chuskas and Red Mesa Valley appear to have been generally unfavorable during this period in which they, too, saw significant immigration, so clearly rainfall totals weren’t the only factor.

They also discuss violence, noting that there is very little evidence for it in this region, particularly in the central Chaco Basin, during Pueblo I, especially compared to areas further north where burned structures are common. There are more burned structures in the Chuskas and near Mount Taylor, on the edges of this region, however, and it is possible that the lack of them in the central basin relates more to the lack of construction wood than to any lack of violence. The authors suggest that, given the known evidence for strife and community abandonment in the Mesa Verde region, one attraction of the Chaco Basin might have been its relative emptiness, which may have drawn people into this much harsher and less fertile region. There’s a general tendency for settlement to cluster around drainages and particularly at confluences of drainages, likely because these locations offered the best agricultural potential in a very dry area even by Southwestern standards. Regardless of what it was that initially drew people into this area, it’s becoming increasingly clear that this influx of population was a key factor in the later rise of Chaco.

Peñasco Blanco Framing Huerfano Mesa

The authors also discuss visibility and sacred geography, which has been a key concern of Van Dyke’s in her previous work. Many of the prominent community buildings in late Pueblo I sites in this region, whether or not they can be considered “great houses,” are situated in locations where important regional landmarks can easily be seen. This indicates that the concern with visibility associated with later Chacoan great houses likely had its roots in this period.

Finally, the authors summarize community settlement patterns in the region. One interesting pattern they note is that in late Pueblo I communities great houses and great kivas don’t tend to occur together, with great houses being more common in the Chaco Basin and great kivas in the Red Mesa Valley. This suggests that two different community integration systems may have been in place in the region during this time. The great house pattern at more northerly sites is interesting in the context of the “proto-great-houses” apparently present at some Dolores area communities further north, especially McPhee Village, and it’s quite likely that there is a direct connection between the two. Great kivas are also common further south, and while they were present at some Mesa Verde Pueblo I sites they weren’t very common. This suggests that at least some of the Red Mesa Valley late Pueblo I communities were in fact settled by immigrants from the south rather than from the Chaco Basin. Some of the earliest communities showing both features were in Chaco Canyon, and it may well be that one factor in the rise of Chaco was the ability of emerging elites there to combine the two traditions into a new social and ideological system, one that would spread far and wide, remaking the course of Southwestern prehistory.

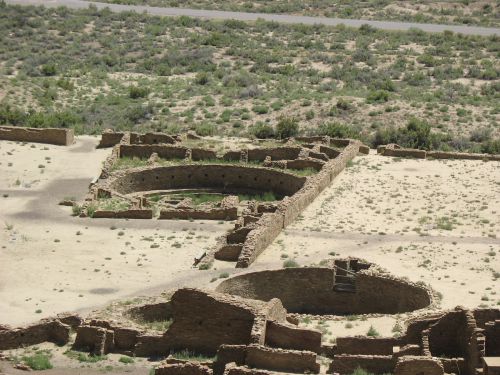

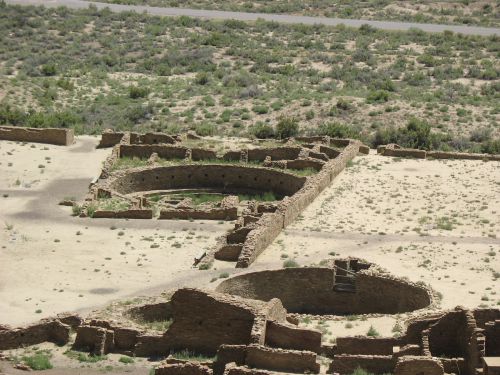

Great Kivas A and Q, Pueblo Bonito

Read Full Post »