Spruce Tree House, Mesa Verde

Although Chaco Canyon is one of the most important places in the United States where the remains of the impressive achievements of the prehistoric Anasazi people are preserved and open to the public, it is by no means the best-known or most popular. Indeed, outside of the southwest Chaco is actually quite obscure. I found this surprising when I first began to work there; having grown up in the southwest, I had sort of always known about Chaco. Not in much detail, but it was always part of my understanding of the world. It turns out, however, that people in other parts of the country, unless they’re particularly interested for some reason in southwestern archaeology, generally just haven’t ever heard of Chaco.

Oak Tree House, Mesa Verde

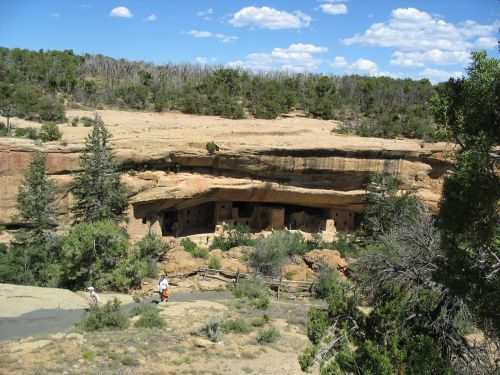

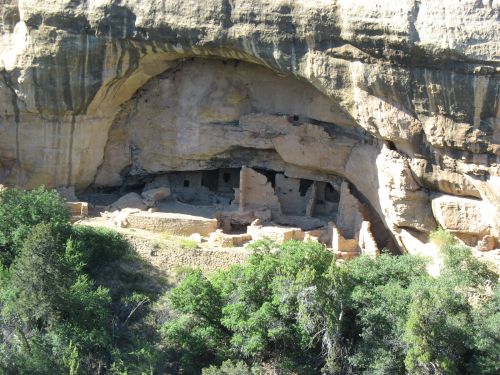

Not that they’re unaware of the Anasazi, of course. But it’s not the Chaco Anasazi of the San Juan Basin that get the most public attention and tourist visitation. Much better known are the cliff dwellings of Mesa Verde. Indeed, for a lot of people “Anasazi” and “cliff dweller” seem to be basically synonymous. We would get a lot of people at Chaco asking if there were any cliff dwellings there. (The answer is no.)

Cliff Palace, Mesa Verde

Cliff dwellings are, indeed, quite spectacular, and it’s no surprise that they would attract much more attention than other settings. They are not very practical places to live, however, and very few people even among the Anasazi ever lived in them. The vast majority of cliff dwellings known in the southwest date to a very short period of time, roughly the last half of the thirteenth century AD, after which much of the Colorado Plateau, including Mesa Verde, seems to have been totally abandoned. Throughout this period, even when the cliff dwellings were occupied, the vast majority of people in the region lived in other types of sites, generally large, aggregated villages.

Square Tower House, Mesa Verde

So why do cliff dwellings get so much attention? One reason is that they’re much better-preserved than open sites. The shelter of the cliff alcoves in which they are located protects cliff dwellings remarkably well, so that when they are excavated they tend to yield an astonishing variety of well-preserved material, including perishable materials like wood, cloth, and feathers. As a result, excavations of cliff dwellings have provided a huge amount of information about the daily life of their inhabitants. Chacoan great houses, due to their large size and fine construction, tend to preserve material better than most open sites as well, but nowhere near as well as cliff dwellings do.

Far View Visitor Center, Mesa Verde

In addition, many of the cliff dwellings, especially at Mesa Verde, were very actively promoted as tourist destinations by local entrepreneurs and guides, especially the Wetherill family of Mancos, Colorado (which also played a key role in early excavations there and elsewhere, including at Chaco). Their spectacular settings and amazing preservation make cliff dwellings interesting even to those who have little interest in archaeology in general, so it was easy to make Mesa Verde and other areas with cliff dwellings into major tourist attractions, especially if they were in relatively close proximity to towns. Since Chaco had none of these advantages, it has languished in relative obscurity.

Mesa Verde from Durango, Colorado

The fact that Mesa Verde gets so much attention now, however, shouldn’t obscure the fact that, except perhaps for a brief period in the thirteenth century, it was never a very important place in the region. During the heyday of Chaco in the eleventh and early twelfth centuries Mesa Verde, while occupied at a fairly high level of population, was decidedly marginal compared to Chaco. After the fall of Chaco it appears to have gained in prestige, and it may have been something of a local center for a while, but even at that time it’s likely that Aztec and other sites in the Totah region between Chaco and Mesa Verde were more important overall.

Far View Communities Sign, Mesa Verde

Considering this context, one obvious question arises: What, exactly, was the nature of the relationship between Chaco and Mesa Verde? Visitors at Chaco, especially those who have just visited Mesa Verde (which is a lot of them), often ask this and related questions. It’s rather confusing, because the information presented at Mesa Verde is very centered on Mesa Verde itself and doesn’t discuss much about the regional context, so people often get the sense that Mesa Verde was a lot more important than it actually seems to have been. When they come to Chaco and see all this talk about how important Chaco was, they start to wonder how to reconcile the rather different stories they are getting at the two places.

Upper-Story Doorway at Far View House, Mesa Verde

So what was the relationship between the two? The short answer is that no one knows. This has been a very difficult topic to deal with in southwestern archaeology, especially since research on Chaco and research on Mesa Verde have generally been conducted by different people and institutions, with the resulting differences in focus and interpretation making it hard to combine the (voluminous) data on the two areas into a coherent whole. Even recent attempts to synthesize data on the relationship have not been able to accomplish much.

Back Wall of Far View House, Mesa Verde

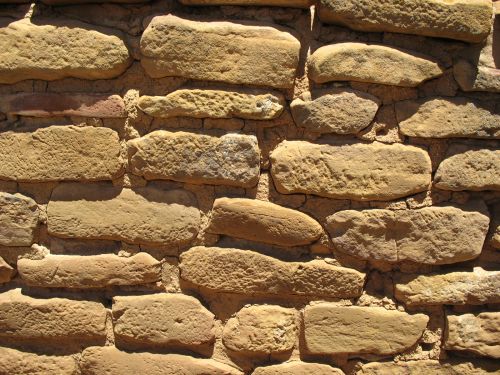

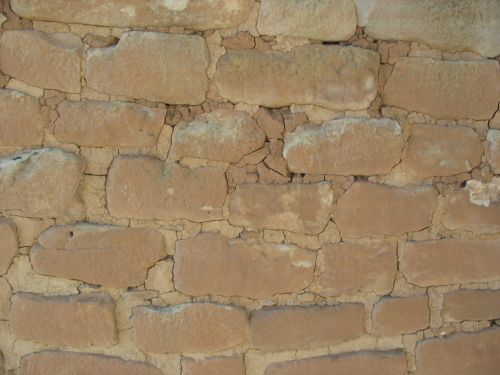

One of the odder aspects of the situation is that there is remarkably little evidence of Chacoan influence at Mesa Verde itself. While there are Chacoan outliers all over southwestern Colorado, and some of them show considerable evidence of quite direct and substantial influence from Chaco itself, the only site at Mesa Verde that has been suggested as a possible outlier, Far View House, shows only a rather vague resemblance to Chacoan architectural styles. While its layout is rather similar to a McElmo-style Chacoan site, and its masonry is sort of McElmo-like as well, it’s much cruder than at many other likely outliers in Colorado that are even further from Chaco, such as Escalante and Lowry to the north. It certainly looks like Far View House was inspired by Chacoan ideas in some fashion, but it really doesn’t look like Chaco itself had much to do with it. It looks more like a local imitation of Chacoan style, made by people who were aware of Chaco and its style but didn’t know much about the details of it.

Masonry at Far View House, Mesa Verde

One of the really weird things about this is that, while Mesa Verde is rather distant from Chaco and correspondingly shows little Chacoan influence or evidence of having been incorporated into a Chacoan system of any kind, other sites further away, and in the same direction, show much more evidence of having been part of such a system. While many of the furthest outliers, such as Edge of the Cedars, look like local imitations similar to Far View House, others, such as Lowry and Chimney Rock, are among the most clearly Chacoan-influenced outliers around, despite being among the most distant.

Masonry at Escalante Pueblo

This suggests that if the Chacoan system was a reasonably well-integrated network with social or political aspects, its boundaries were quite complicated. It apparently included the whole southern San Juan Basin as far north as the San Juan River, the whole middle and upper San Juan valley and the valleys of the major northern tributaries of the San Juan, and the Dolores River valley and Great Sage Plain further north, but not Mesa Verde, which lies right between the San Juan and the Great Sage Plain.

Masonry at Lowry Great House

The implications of this are hard to understand, but one possibility is that the system was not, in fact, as well-integrated as it might seem at first glance, and that it may have been more a network of independent small polities loosely affiliated through adherence to a common social system or religious cult centered on Chaco. This type of explanation has been pretty popular in Chacoan research over the past few years. Another explanation, less popular these days, is that Chaco was a single integrated polity with far-flung and complicated boundaries, and that the people of Mesa Verde resisted its expansion and were never fully incorporated into it, so it expanded around them instead. At this point it’s hard to say which of these is more plausible, and it’s quite possible that the real answer is something totally different from either.

McElmo-Style Masonry at Casa Chiquita

One interesting sidenote is the odd and somewhat ambiguous evidence for continued Chacoan influence in Colorado even after the fall of Chaco itself. Great houses, or structures that sort of resemble great houses, at least, continued to be built well into the 1200s in the Mesa Verde area, and it’s possible (though highly speculative) that part of the rise of Mesa Verde in the thirteenth century, to the extent that it did rise to regional prominence, was tied to a revival of Chacoan ideology symbolized by the construction of D-shaped structures with apparent ritual purposes.

Masonry at Spruce Tree House, Mesa Verde

The best known of these structures is probably the Sun Temple at Mesa Verde itself, which seems to be associated with Cliff Palace and which also seems to have some astronomical alignments. Interestingly, the masonry at the Sun Temple looks a lot more Chacoan than anything at Far View House, despite the fact that the Sun Temple was built long after Chaco had faded into obscurity and the fact that other sites built at Mesa Verde at the same time, such as Cliff Palace and Spruce Tree House, have much cruder masonry.

Masonry at the Sun Temple, Mesa Verde

There are a lot of questions remaining about this issue, and much more research remains to be done, but there are some tantalizing hints that untangling the connections between Chaco and Mesa Verde may shed light on a whole slew of continuing mysteries about the prehistory of the southwest. There’s enough there to keep archaeologists busy for a long, long time.

Pipe Shrine House with Far View House in Background, Mesa Verde