Civil Engineering Plaque at Mesa Verde

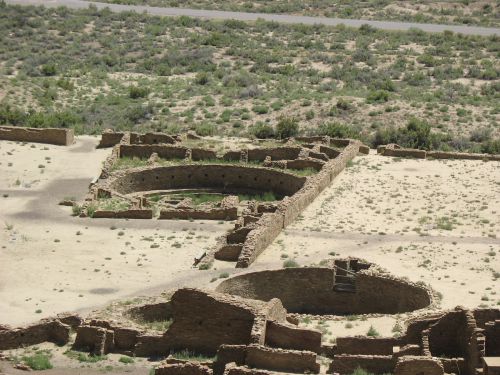

I’ve previously discussed water control technologies at Chaco, where they were particularly important given the extreme aridity of that area even by Southwestern standards. There is abundant evidence, however, that water control was a widespread activity throughout the ancient Southwest, even in areas with more reliable water sources. The best-studied water control systems have been the impressive large-scale canal systems built by the Hohokam in southern Arizona, but less elaborate systems are known in the northern Southwest as well.

Among the better-studied of these systems are those in the Mesa Verde area of southwestern Colorado. In comparison to Chaco especially this area is much more suitable for agriculture. The Mesa Verde proper in particular is high enough that it gets quite a bit of regular precipitation, and it is generally thought that the majority of agriculture on the mesa throughout its occupation was dry farming on the mesa top, depending only on direct rainfall. Interestingly enough, however, there is extensive evidence of water control features even in this more favorable environment. A detailed description of some of them can be found in an article by Arthur Rohn published in 1963. He focused on two main types of soil and water control: checkdams forming small terraces, presumably agricultural, along intermittent drainages and large reservoirs, probably for domestic water. The checkdams, which have since been discovered in other parts of the greater Mesa Verde region such as Hovenweep as well as other regions of the northern Southwest (including Chaco), consisted of small masonry walls, laid without mortar, which served to hold back water and soil which would otherwise drain right off the mesa top during rainstorms. Some drainages had dozens of these, typically about a yard high and a few yards apart. Most had been breached at some point after the abandonment of the area and were visible only as rock alignments of varying lengths and heights, but some apparently still held soil and water back well enough that they were covered in vegetation, preventing Rohn from observing much about them. The agricultural function of these terraces is suggested by the frequent association with them of small structures generally interpreted as seasonal field houses.

Checkdam, Hovenweep National Monument

It is not at all clear, however, why the people on Mesa Verde would have needed to go to the effort to build all these terracing systems when they had so much fertile land right on the mesa top. Rohn calculated that the likely extent of the terraces added only about 1% of the total area of tillable land on top of the mesa. He suggested several potential reasons for their construction, including depletion of mesa-top soils, increasing population and subsequent need for more intensive farming, and cultivation of specialized crops of high value that made the additional effort invested in constructing the terraces worthwhile. Ultimately, however, Rohn had insufficient data to come to any firm conclusions about the purposes of the terraces, and as far as I can tell the situation has not improved much since his time despite the much more extensive paleoclimatic data now available.

The other water control features that Rohn described were the large reservoirs associated with certain of the more densely populated areas of the mesa. Most of these consisted of large dams, much larger than the small checkdams, across certain canyon heads, where they likely impounded water either for use right there or to soak down through the porous sandstone to feed springs underneath. These reservoirs thus used the natural characteristics of the canyon heads and required relatively little additional effort to store water for human use.

Far View Reservoir, Mesa Verde

The best-known reservoir on Mesa Verde, however, which Rohn described in detail, was quite different. Rohn called it Mummy Lake, which was the standard name for it in his time, but it is now often known as Far View Reservoir. This is a large oval masonry structure, of mostly artificial construction and about 90 feet in diameter. It is near the cluster of sites known as the Far View Group, including Far View House, which is often claimed to be an outlying Chacoan great house. These sites mostly date to the Pueblo II period in the eleventh and early twelfth centuries AD (contemporaneous with the height of the Chaco system), which makes them earlier than the most impressive sites on the mesa, which date to the Pueblo III period (late twelfth and thirteenth centuries AD) when Mesa Verde apparently had its highest population.

Far View Reservoir Intake Channel, Mesa Verde

Far View Reservoir was apparently not used for agricultural irrigation, as it has an intake channel but no outlet. It was fed by an elaborate canal system upstream that channeled water to down the mesa. Rohn noted that the intake channel was of quite sophisticated design:

The feeder ditch coming from the north did not empty directly into the north side of the reservoir, but rather ran by the west uphill side until it met the mouth of the intake channel at the southwest corner. There water was diverted into the inlet around a right-angle turn and conducted in a northeasterly direction into the reservoir. Such a complicated maneuver caused the suddenly slowed water to drop its silt burden in the intake channel, which could be easily dredged, rather than in the deepest part of the reservoir, where dredging operations would be difficult and would muddy the water.

Trenching of the reservoir by Earl Morris in 1934 revealed that the original bottom lay about 12 feet below the intake. This would give the reservoir a maximum capacity of about 76,000 cubic feet, equivalent to about 1.74 acre-feet or 568,000 gallons. That’s a lot of water.

Since there was no outlet from the reservoir, it presumably didn’t feed a system of irrigation canals. What, then, was this water for? Rohn’s answer, with which most other archaeologists have agreed, was that it was used for domestic water. Trenching of the walls of the reservoir revealed pottery of Pueblo II date, contemporaneous with the nearby Far View sites, which makes sense. A small ditch led off from the main ditch leading to the reservoir, emptying some of the water diverted from upstream into a small drainage with a series of checkdams similar to those documented elsewhere on the mesa, which were presumably farmed by the Far View residents. Most of the water, however, went into the reservoir, from which it could be easily extracted with pots and brought home for cooking and other daily uses. Residents of other parts of the mesa seem to have used nearby springs (perhaps fed by canyon-head reservoirs above them) for their domestic water, but there are no springs near the Far View group, so this elaborate reservoir seems to have been built to support the community there, which as Rohn pointed out was the largest concentration of population on this part of the mesa before the Pueblo III period.

Cliff Palace, Mesa Verde

At some point in late Pueblo II or early Pueblo III a very elaborate ditch was built carrying water from the Far View area south almost to the very end of the mesa. This ditch skirts the Far View sites, suggesting that they were still occupied when it was constructed, but it heads toward the major cliff dwellings to the south that became the major focus of occupation in late Pueblo III. It’s not clear exactly what this ditch led to, but the fact that it heads toward the major cluster of sites including Cliff Palace, in an area with few springs but a very large population during late Pueblo III, suggests that it likely supplied domestic water for these sites, especially after the abandonment of the Far View sites allowed the intake channel to Far View Reservoir to be blocked and all of the water from the whole system to be brought south.

Rohn mentioned in his article that while Far View Reservoir is the only such reservoir known from this part of Mesa Verde proper, there are several other such facilities known from elsewhere in the region, especially in the Montezuma Valley to the northwest. A more recent article by Rich Wilshusen, Melissa Churchill, and James Potter (from 1997) provides a valuable summary of information known on reservoirs throughout the region, as well as detailed information on one reservoir studied intensively by the Crow Canyon Archaeological Center. This reservoir is known as Woods Canyon Reservoir after Woods Canyon Pueblo, a late Pueblo III site nearby. Also in this general area are a Chaco-era (late Pueblo II) outlying great house known as the Albert Porter site and a site called Bass Ruin that apparently dates to the poorly understood early Pueblo III period, in between the decline of Chaco and the rise of the large aggregated pueblos and cliff dwellings in late Pueblo III. This reservoir much less elaborate than the Far View one, consisting merely of an earthen dam built across a natural drainage, impounding the water behind it.

Excavation of both the dam and the impounded reservoir area, along with surface collection of sherds, showed that the dam was likely constructed during early Pueblo III or possibly earlier. An innovative use of tree-ring dates from trees growing on top of the dam in the 1950s, which must have begun growing after the reservoir no longer held water, put the date of dam failure at no later than about AD 1350. Assuming that it would have taken a century or two for the reservoir to fill with enough sediment for the dam to fail, the authors put the likely usage of the reservoir in early Pueblo III. These two lines of evidence converge nicely.

White Ware Bowls at Chaco Visitor Center Museum

Another striking aspect of the potsherd evidence was the extraordinarily high prevalence of white wares (77%) and of jars (71%). The predominance of white wares and the low occurrence of gray utility wares suggests that most of the sherds came from white ware jars used to carry water from the reservoir to habitation areas which broke in the process, and the lack of bowls shows that those habitation areas were not in the immediate vicinity of the reservoir. Habitation sites usually have assemblages consisting mainly of gray ware jars, which were used for cooking, with large numbers of white ware bowls, which were used to serve food, as well. The authors mention that previous work at Far View Reservoir (after Rohn) had shown a similar distribution of ceramic wares and forms, and the few sherds mentioned in Rohn’s article also show this distribution. Given this, as well as the lack of nearby canals or soils suitable for farming, the authors conclude that this reservoir was likely used primarily or solely for storage of domestic water, as Rohn had argued for Far View Reservoir. They also note that the dating was surprisingly early; these reservoirs are usually found in association with late Pueblo III aggregated sites, and there has been a frequent assumption that they served those communities. The evidence from Woods Canyon, however, suggests that the reservoir was actually constructed well before Woods Canyon Pueblo, at a time when the local population lived at Bass Ruin or even in the Chacoan community around the Albert Porter site.

Gray Ware Jars at Chaco Visitor Center Museum

In addition to this interesting information about this one reservoir, the authors collected all the information available at the time on other reservoirs in the Mesa Verde region, including the extensive information published only in the so-called “gray literature” (i.e., reports from salvage excavations and other cultural resource management projects that are not easily available to the general scholarly community). From this data set they find that there are two main categories of reservoirs: those built as integral parts of late Pueblo III aggregated villages and those like Wood Canyon Reservoir built near such villages but probably dating to an earlier period and associated with Chaco-era or immediate post-Chaco communities. This implies that these large reservoirs may not have been a response to drought as climatic conditions deteriorated in the twelfth and thirteenth centuries, as is often assumed, but that they may instead have been monumental public architecture, like great houses, great kivas, and roads, associated with Chacoan communities and used to sustain the large populations of those communities. As conditions did deteriorate, however, the existence of these communities and their dependable water sources may have encouraged others to join them, leading to the well-known process of aggregation and formation of large villages during the late Pueblo III period.

Furthermore, the creation of these large, permanent features would have required substantial labor and indicated a commitment of a community to a particular location for the long term. This was likely a new development in the northern Southwest during Pueblo II, perhaps associated with Chacoan influence; previously, sites had been mostly occupied for quite short periods of time, and people seem to have moved very frequently. From the eleventh century on, however, the trend is toward increasing commitment to particular localities, although the actual sites in which people lived didn’t necessarily last very long. Multiple sites occupied one after another in a given area, with the general trend toward increased aggregation and more defensive locations, is typical throughout the Mesa Verde region in the period between AD 11oo and 1300, when the whole area was abandoned. The role of Chaco Canyon, which is both one of the longest-occupied areas in the prehistoric Southwest and one where water control is most necessary, in all this is interesting to ponder.

Pueblo Bonito and Basin with Captured Rainwater

Finally, it’s worth noting the distinction between different uses of water here. The largest quantities of water would have been needed for agriculture, but only at certain times of the year, and with careful planning the seasonal rains and spring runoff could be harnessed to adequately water the crops. The amount of water needed for domestic use was much smaller, but it was needed all the time. Springs were likely adequate for domestic use as long as populations remained small, but as larger communities developed in some areas with few springs more elaborate measures were necessary to ensure sufficient water was available at all times. This was most obvious in very dry places like Chaco, but even better-watered areas like Mesa Verde began to have to deal with these issues as population increased and the climate changed.

Rohn, A. (1963). Prehistoric Soil and Water Conservation on Chapin Mesa, Southwestern Colorado American Antiquity, 28 (4) DOI: 10.2307/278554

Wilshusen, R., Churchill, M., & Potter, J. (1997). Prehistoric Reservoirs and Water Basins in the Mesa Verde Region: Intensification of Water Collection Strategies during the Great Pueblo Period American Antiquity, 62 (4) DOI: 10.2307/281885

Read Full Post »