“Pithouse Life” Sign at Mesa Verde

Chapter 10 of Crucible of Pueblos, by Richard Wilshusen and Elizabeth Perry, looks at the position and roles of women in early Pueblo society, with a particular focus on how those roles seem to have changed with the economic and demographic changes of the late Basketmaker III and early Pueblo I periods that recent research is bringing into focus. It’s a thought-provoking chapter but in some ways rather odd, with many of its most intriguing proposals resting on what seems like fairly thin evidence.

The chapter looks at three main topics: food production, human reproduction, and gender relations in social power. Its overall thesis is that in the northern Southwest between AD 650 and 850 interrelated changes in food production systems and human reproductive rates led to major changes in gender roles, particularly regarding the division of labor between men and women, that may have led to settlement aggregation into villages and to changes in social power related to trade and ritual. The resulting social structure, in place by the end of the Pueblo I period in at least some areas, was the earliest form of the “Pueblo” society as known from modern ethnography, with its strict division of labor by gender and extension of this gendered ideology to many other domains of life.

Of the three main topics, the authors devote the most attention to the first, and it’s here that their arguments are strongest and most clearly supported by the archaeological evidence. The key change in food production during the period in question is the intensification (not introduction) of maize agriculture as the primary subsistence activity, supplemented by the growing of other crops like beans and squash, by the raising of domesticated turkeys, and by hunting and gathering of wild foods. Recent research has clarified the sequence and extent of this change, although a lot of questions still remain.

As the authors note, one of the most puzzling results of research on early agriculture in the northern Southwest is that maize is now clearly established as having been introduced as early as 2000 BC in several widely spaced parts of the Colorado Plateau (including Chaco Canyon), but for hundreds of years it appears to have remained a minor part of the diet of the groups that used it. It was only in the Basketmaker II period, between 300 BC and AD 300, that maize use became widespread, and even then, according to Wilshusen and Perry, local groups varied widely in the contribution of maize to their diets. There may have been a distinction between immigrant groups from the south that had a heavily agricultural subsistence base and local hunter-gatherers who were gradually incorporating some farming into their lifestyles.

This slow and incomplete adoption of agriculture is in contrast to the situation in other parts of the world where agriculture, once introduced, spread rapidly and quickly replaced hunting and gathering. It’s still not clear why, although Wilshusen and Perry note that as a tropical plant originating in Mexico, maize would have been poorly suited for the harsher climate of more northern latitudes, and that it would have taken some time for people to breed hardier varieties. It is also apparent that the variety of maize initially introduced was small and not as obviously superior to local wild plant foods as later varieties, and that it was initially introduced without an accompanying “package” of other domesticated foods, as was the case with agricultural spreads in other areas. Domesticated squash seems to have been introduced not long after maize, but separately, and domesticated turkeys appear to have been introduced from a different direction altogether, although the timing and details of their domestication remain very murky.

Be that as it may, the main point Wilshusen and Perry make in regard to this slow adoption of maize is that it is likely that women, who based on cross-cultural studies of hunter-gatherers tend to be responsible for gathering of plant foods, were involved in the initial use of maize in the northern Southwest. However, this small-scale introduction of a new food, even one associated with a new type of food production, probably wouldn’t have had a major impact on existing gender roles or division of labor. That would come later.

The full “Neolithic package” appears to have arrived in the northern Southwest between AD 300 and 600, with components including a larger, more productive variety of maize known as Harinosa de Ocho; beans, newly introduced from the south; greater use of turkeys for both meat and feathers; and greater investment in facilities for food storage and processing. The greater productivity enabled by these innovations led to rapid population growth and the spread of agricultural groups over the landscape, in striking contrast to the lack of such growth with the initial introduction of maize much earlier. Wilshusen and Perry associate these developments with the transition from Basketmaker II to Basketmaker III, as well as with the major changes in the roles of women that they document.

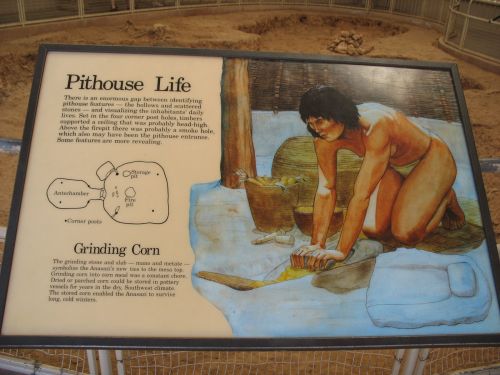

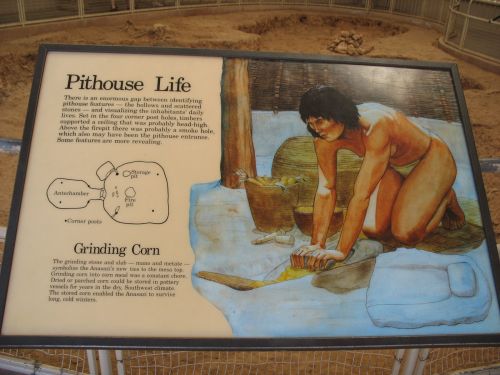

Additional support for these changes in food production come from complementary changes in storage facilities and grinding tools. As documented in the well-studied Dolores area, the importance of storage seems to have risen over the course of the late Basketmaker III and Pueblo I periods from AD 650 to 875. Storage facilities changed from small pit rooms isolated from the main dwellings to more secure and more solidly built storage rooms directly attached to living rooms and only accessible from them. These typically consisted of two storage rooms at the back of each living room, the beginning of the “suite” layout that would continue to be a key architectural feature into Chacoan times. It is possible that at least initially these paired rooms were used to store two years’ harvests, one in each room, so as to provide a subsistence buffer against drought and other unexpected problems.

There was also a shift over this period in grinding implements from basin metates with one-handed manos to much more efficient trough metates with two-handed manos. Beyond this shift, a greater variety of grinding tools became common over time. Together with the storage data, this indicates an increased importance of grinding as a component of food preparation. In the modern Pueblos grinding is a female-associated activity, part of an overall suite of food-preparation tasks accomplished by women that also includes shucking, shelling, drying, and storing corn. Of these tasks, however, grinding is considered particularly important to the female role, and it is an important part of female puberty ceremonies (of which the Navajo Kinaaldá, of clear Pueblo origin, is probably the best known). Men, on the other hand, are responsible for planting and harvesting the corn, as well as protecting the fields. This seems to be a change from the presumed hunter-gatherer system in which women were generally responsible for gathering plant foods as well as processing them, and Wilshusen and Perry suggest that it may have arisen in early Pueblo times as fields at greater distances from residence locations in villages became increasingly vulnerable to attack by enemies, prompting men’s role as warriors to encompass guarding fields and, in time, tending them as well.

Another important female task in modern Pueblos is making pottery, and this too seems to have become increasingly important with the expansion of agriculture in early Pueblo times. With more use of crops and additional cultigens such as beans, pots would have become more important for food preparation, and with the number of vessels needed and their short use-lives of 1 to 6 years women would have had to be constantly making new ones. (This is of course assuming that most pots for domestic use were made by the family unit itself, which may well be true for this early period but was not necessarily later on.) Based on detailed study of an isolated Pueblo I hamlet in the Central Mesa Verde area, Wilshusen and Perry estimate the following assortment of vessels for a typical household at any given time:

- 2 to 7 small cooking jars

- 1 to 4 medium cooking jars

- 0 to 2 large cooking jars

- 1 bowl

- 0 to 3 ollas for water

- 2 to 3 other vessels

- 10 to 20 sherds from broken pots used as containers or tools

Keeping a household supplied with all these pots would have been a major part of a woman’s domestic labor, in addition to the food processing tasks mentioned above, along with other major responsibilities such as caring for children.

And speaking of children, Wilshusen and Perry go on to discuss human reproduction and the apparent changes in it associated with the other changes they identify. The two main changes they note are shifts in the use of cradleboards and an apparent increase in the societal fertility rate. This part is somewhat less thorough than the food production part of the paper, but it does still identify some intriguing evidence for change.

First, cradleboards. The authors note that study of these items, in which infants were bundled while they were very young, has been surprisingly limited, despite their relevance to an important event that has long been recognized: the beginning of evidence for “cranial deformation,” or the reshaping of skulls as a result of prolonged contact with certain kinds of cradleboards in infancy. The shift from “undeformed” to “deformed” (the terminology is very problematic, as there is no evidence of health problems from the practice) crania is traditionally associated with the transition from Basketmaker III to Pueblo I, and early in the history of Southwestern archaeology the change in head shape was even taken as evidence for a population replacement. (That was in the early twentieth century when anthropologists put much more emphasis on skull shapes in defining populations than they do now.) It is now generally thought that the distinction is actually due to the use of soft versus hard cradleboards, but recent research that Wilshusen and Perry discuss suggests that both types of cradleboards were present in both Basketmaker and Pueblo times. Thus, the shift in cranial shape is actual due not to a change in the type of cradleboard but in how it was used. The main changes that actually seem to have occurred in the Pueblo I period are:

- Foot rests on cradleboards disappear.

- Hoods become more common.

- Construction is more expedient.

According to Wilshusen and Perry, these changes together indicate that women had less need to move while carrying children in cradleboards, but that they needed more cradleboards overall, possibly indicating that they had more children. This part of the paper does not go into much detail about where these conclusions come from, but the overall conclusions is that this is further evidence that women were more tied to the domestic sphere in Pueblo I, and possibly that they had more children.

On that note, demographic data appear to indicate that the population increases seen in at least some part of the Pueblo world during Pueblo I were due largely to natural increase after initial immigration into new areas. The best data come from the Central Mesa Verde and Eastern Mesa Verde areas, both of which seem to show this pattern. Prehistoric demographics are notoriously hard to reconstruct, but based on the large recent data sets from major excavation projects Wilshusen and Perry propose that a Neolithic Demographic Transition (a major increase in fertility associated with the beginning of intensive agriculture) began in the northern Southwest around AD 300, with major consequences over time for women in particular, given their gender-defined economic roles. This is comparable to evidence seen in other parts of the world with the beginning of agriculture. The key point here for the role of women is that with increasing rates of both childbirth and survival of children beyond infancy, families would have become larger, increasing the amount of domestic labor required of women to maintain their households given the gendered division of labor presumed to have developed. This would be one explanation for the increased importance of food processing mentioned above.

Finally, Wilshusen and Perry talk about exchange and social power. The discussion here is very abbreviated, and relies heavily on references to the next chapter in the book (which is a little odd), but the basic idea is that rock art evidence shows a shift in social power to male leadership of ritual in late Basketmaker III, continuing into Pueblo I. Female economic roles expressed in matrilocal residence may have driven men to make external trade alliances, which over time developed into new ritual systems focused on important lineages within villages rather than large public rituals at central places not necessarily associated with a specific lineage or community. Matrilineal lineages were still important, and the focus of key rituals, but changing gender roles may have involved an increased role for the men of the lineage in certain types of rituals. Burial evidence from Ridges Basin may support some of these ideas, with striking differences in male and female burials, particularly in the types of exotic goods included. Both women and men were buried with exotic items occasionally, but the specific types of items varied, suggesting gendered access to different trade systems. There are also geographic differences within the basin suggesting different community connections and ideological systems. This section is intriguing but very sketchy, even compared to the rest of the paper. More detailed discussion of some of these ideas will have to wait for the next chapter.

Overall, the conclusion of this chapter is that over the course of the early Pueblo period gender roles shifted in a way that evolved into the system(s) that are well known from the modern Pueblos. This may have been a response, in part to the demographic shift resulting from the development of intensive agriculture, with its resulting higher birthrates and changes to the roles of women. Women’s labor was key to this transition, but it’s not clear that it was actually good for women as a class on net. There has been some discussion of the idea of “parallel status hierarchies,” in which men and women had different tasks but both allowed meaningful status through high achievement. However, later evidence from Pueblo sites shows that women were often excluded from access to high-value resources such as meat, and that their graves were generally less elaborate than men’s (a contrast to the Pueblo I situation in at least some areas). It doesn’t appear that many strictly comparable studies of these issues have been done of the Pueblo I period itself, so it’s hard to say how these changes felt for the women who were living through them. The authors of this paper seem to lean toward thinking the changes were not actually beneficial for those women, but the evidence is thin enough that it’s not clear.

Above I have summarized the arguments of this chapter as best I could, but it’s worth noting that the argumentation of the chapter itself is highly abbreviated, and summarizing it has required a lot of assumptions and interpretive leaps. It kind of reads like this paper is an abbreviated version of a longer argument, with some important parts left out. Nevertheless, it raises a lot of interesting questions that have rarely been addressed in Southwestern archaeology, especially regarding the early Pueblo period, and for that alone it is valuable.

Read Full Post »