Sleeping Ute Mountain and Surrounding Landscape from Four Corners

If you stand at the Four Corners monument and look in the direction of Colorado you will see Sleeping Ute Mountain dominating the view. From this direction you are looking at the southwest side of the mountain, and in front of it you see the southern piedmont. On the right side of the piedmont, though not visible from this distance, is Cowboy Wash. It’s one of several ephemeral streams running from the mountain itself across the piedmont to the San Juan River.

One thing that might strike you about the view from this perspective is that it looks like an awfully dry, desolate, uninhabitable wasteland. And you would be correct to think that. The southern piedmont of Sleeping Ute Mountain is an extremely arid and inhospitable environment even by the standards of the Southwest, which is saying something. It’s only a few miles from Mesa Verde to the east and the Great Sage Plain to the north, both areas that get relatively abundant rainfall and supported large and prosperous prehistoric communities, but it is worlds away from them environmentally. While those areas get sufficient rainfall to support dry farming, and the Great Sage Plain is commercially farmed even today, the southern piedmont does not, and any type of agriculture there would have to rely on some sort of irrigation. Today the Ute Mountain Ute tribe has a large irrigation project in the area, using water brought in from McPhee Reservoir, 45 miles to the north, via the Towaoc Canal. The construction of the reservoir and the canal was part of the Dolores Project, which involved substantial archaeological excavation of the inundated area that significantly improved archaeological understanding of the prehistory of the region. This work took place from 1978 to 1985 and was known as the Dolores Archaeological Project, the largest salvage archaeology project in US history.

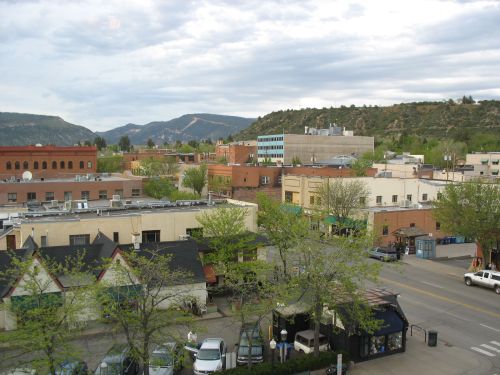

McPhee Reservoir, Dolores, Colorado

The creation of the irrigated fields on the piedmont resulted in further salvage excavations in the 1990s. Among the sites excavated was 5MT10010, which contained considerable evidence of a gruesome incident of probable cannibalism around AD 1150. It is not the only site in the area to show evidence of cannibalism during this period; in fact, three other sites in the same community, excavated slightly earlier in connection with the construction of the canal, also showed evidence of having been destroyed in an incident involving extensive processing of human remains in a way suggesting cannibalism, and there are several other sites in the area showing similar assemblages, most from the same period but at least one from a later period. It is at 5MT10010 that the most solid evidence for actual cannibalism, as opposed to processing of bones in a way that may or may not indicate actual consumption of human flesh, in the form of a coprolite that tested positive for the presence of human muscle tissue.

There are many questions that arise from these findings, but one of the most puzzling is also one of the simplest: what were people doing living at Cowboy Wash in the first place, and how did they manage it? After all, they weren’t building giant dams and canals of the sort involved in the Dolores Project. In many parts of the Southwest, especially upland areas like Mesa Verde, dry farming using only rainfall was standard during this period, and water control techniques were generally used only for domestic water if a nearby spring or other reliable source was not available. There are a few springs on the southern piedmont that probably would have supplied sufficient domestic water for the small number of people living there, but the rainfall would definitely not have been sufficient to farm with. The only source of water at all sufficient for agriculture would have been the occasional floods, from spring snowmelt and summer thunderstorms, that would flow through Cowboy Wash itself and the other drainages on the piedmont. None of these flows permanently today, and there is no evidence that they ever did. As at Chaco Canyon, then, which is similarly dry, farming would have to have been based on some sort of technique for capturing the floodwater.

Flowing Chaco Wash and Cliffs below Peñasco Blanco

There are a variety of ways this might be done, including diverting the rainwater from cliffs, as was done at Chaco, planting along the sides of the drainage where the floods would regularly overflow the banks, and what is known as “ak-chin” farming, as practiced by the O’odham of southern Arizona, which involves planting right in the path of the runoff at places where the velocity of the water is relatively low, as at the mouths of tributaries to main arroyos. There are no sheer cliffs on the southern piedmont like the ones at Chaco, so probably a mix of overbank and ak-chin farming would have been practiced at Cowboy Wash.

A paper by Gary Huckleberry and Brian Billman addresses the nature of farming at Cowboy Wash, and also addresses a related issue, which is whether periodic entrenchment of arroyos due to drought played a role in the patterns of abandonment and migration that characterize Southwestern prehistory. It is pretty clear by now that the paleoclimatological record shows periods of drought corresponding to periods of abandonment of certain parts of the Southwest, and one proposed mechanism for how this would have worked is that drought would have led to increased erosion and/or hydrological changes in the water table that led to the entrenchment of arroyos, which would have been disastrous for populations dependent on certain types of floodwater farming (especially overbank), as the broad floodplains of the local drainages would have been replaced by deep channels that took the water away quickly instead of letting it overflow to water the crops. Ak-chin farmers would not necessarily have been affected to the same degree, but if the side drainages they used became entrenched as well they would not have been able to use their techniques either. Thus, drought would lead to arroyo-cutting, which would lead people to leave formerly productive areas for others that were less affected. This theory has been proposed as an explanation for certain events at Chaco, with the idea being that some of the social changes late in the Chacoan occupation were due to degradation of the Chaco Wash and the need to change agricultural strategies. The phenomenon of arroyo-cutting in general is richly illustrated in historic times at Chaco. The early reports of the Chaco Wash from the nineteenth century indicate that it was a shallow, meandering drainage, much like the current condition of the Escavada Wash to the north and the “Chaco River” that is formed by the confluence of the two at the western end of the canyon and flows north to the San Juan. By the early twentieth century, and accelerating since then, however, the Chaco Wash through the canyon has cut down significantly and there is a very deep arroyo channel apparent today.

Entrenched Arroyo at Chaco

The drought-downcutting-abandonment theory makes sense as far as it goes, but as Huckleberry and Billman point out there are some problems. For one thing, the extent to which arroyo-cutting is actually linked to drought, rather than other factors including the specific geology of the area, is hotly debated and there is no consensus. The idea that while drought may be one factor causing arroyo-cutting there are other factors involved as well is supported by the fact that in different drainages in the Southwest that have been studied in depth the periods of arroyo-cutting do not necessarily correspond to region-wide droughts or other climatic changes. In some areas they do, but in other areas they don’t. At Cowboy Wash specifically, the available evidence indicates that the wash began to entrench sometime before AD 950, and that it began to refill with sediment sometime between AD 1265 and 1400. If abandonment does in fact correspond to arroyo-cutting, then presumably the Cowboy Wash area should have been abandoned between 950 and 1265, and possibly occupied before and after this. If downcutting results from drought, there should also be evidence of drought during the 950 to 1265 period.

The basic upshot of the Huckleberry and Billman paper is that neither of these expectations is met. The evidence for drought conditions at Cowboy Wash generally matches that for the rest of the region, with the major droughts in the mid-twelfth century and late thirteenth century AD and several smaller droughts at irregular intervals before then. This doesn’t show any particular relationship to the stratigraphic evidence for arroyo-cutting, which seems to have been going on to some degree throughout the period from AD 950 to at least AD 1265. Furthermore, the evidence for settlement doesn’t line up either. The marginal nature of the Cowboy Wash area implies that it would probably not have been occupied for most of prehistory, and this was indeed the case. There were a few ultimately unsuccessful attempts to colonize the southern piedmont, however, and they don’t show any particular relationship to the periods of arroyo-cutting (although they do perhaps relate to periods of drought). The first agricultural occupation of the area came during the Basketmaker III period, when a few pithouses were apparently used seasonally as summer fieldhouses, presumably associated with nearby fields, from about AD 600 to 725. After these were abandoned, at a time which may correspond to a drought, the area does not seem to have been occupied again for more than three hundred years. Then, around AD 1050, a few permanent, year-round sites were built. These seem to have been occupied for only a few years, however, as there was no significant buildup of trash associated with them. After they were abandoned, three larger villages, including one at Cowboy Wash, were established around AD 1075. These had extensive trash deposits and seem to have been occupied for one or two generations. These communities were apparently abandoned, however, when the next occupation began in the 1120s by a population with apparent links to the Chuska Mountain area to the south. This occupation at Cowboy Wash is the community that was apparently destroyed around AD 1150 (again coincident with a major drought) when its inhabitants were mutilated and cannibalized. After this event, the area was once again abandoned until about AD 1225, when two new communities were founded, including one again at Cowboy Wash. Within a few decades the population at Cowboy Wash appears to have aggregated at Cowboy Wash Pueblo, following a typical pattern for the region. Also typical of the region, the whole southern piedmont seems to have been abandoned by AD 1280, at the time of the “Great Drought” that coincides with major changes throughout the Southwest.

Entrenched Chaco Wash from Cliff Top near Pueblo Bonito

So basically, all of the attempts at year-round occupation of the southern piedmont seem to have occurred during the period that Cowboy Wash was being downcut. While these were all ultimately unsuccessful, some lasted for a few decades, so clearly they were able to grow some food at some times. This strongly implies that at least in this case, arroyo-cutting was not particularly linked to abandoned, although drought probably was. Huckleberry address the issue of how farming could have been done during periods of downcutting by looking at Cowboy Wash and its tributaries today. They find that while some portions of the main wash, especially, are indeed heavily downcut, other portions are not, and they label this type of drainage a “discontinuous ephemeral stream,” which is to say, a normally dry wash with some portions that are severely downcut and others that are not. On the uncut portions, which include much of the length of the tributaries, overbank or ak-chin farming could easily be done today, and this was presumably the case in antiquity as well. The hydrology of the area is such that the areas of downcutting would not have been stable, and would have tended to migrate upstream, but the complexity of the system is also such that this would not have made the entire system unusable; while some parts were being newly cut, others would be filling in, and prehistoric farmers would merely have to move their fields around a bit rather than abandoning the area entirely.

All that being said, however, the question of why people were trying to settle this quite harsh and difficult area in the first place. It is interesting to note that the attempts at settlement generally came during periods of relatively favorable environmental conditions, which would have made this area a bit less forbidding than usual, as well as during times of increased regional population, when all the good land may well have been taken and some people were forced to seek out the more marginal areas. The violence that appears to have accompanied the drought of the twelfth century, especially, suggests that when the good times came to an end social relations got very bad very fast. Huckleberry and Billman suggest that the reason people did end up abandoning Cowboy Wash, the times when they were not attacked, was merely drought itself, which they were unable to cope with as well as other populations, even those who also used floodwater farming techniques, because the size of the watershed was relatively small and the amount of rainfall feeding the washes was also small, so the total amount of water they had to work with was much smaller even in good times than at place like Chaco with large watersheds. In that context, even a small decrease in annual precipitation could be devastating, leading to failed harvests and the need to move away.

Non-Entrenched Escavada Wash from New Mexico Highway 57

Indeed, there is evidence that the time of the massacre at Cowboy Wash was very difficult for the people there. Archaeobotanical studies of pollen and other plant remains showed that there was apparently little or no maize in or around 5MT10010 at the time of abandonment, which is quite surprising for a Pueblo site. The plant remains that were there were mostly from wild plants such as chenopod, amaranth, and tansy mustard, all of which would have been available in the spring and likely would have been intensively collected if there were no stored corn available due to a failed harvest the previous fall. In addition to pinpointing the season in which the incident occurred, this implies that times were very tough for the inhabitants of 5MT10010, and perhaps for their attackers too. The coprolite showed no sign of having plant material in it, which suggests that whoever left it had not just eaten some corn at home before setting out to attack 5MT10010.

Another paper associated with the project, by Patricia Lambert, suggests another problem the Cowboy Wash inhabitants apparently had: disease. In this paper Lambert reports on analyses of ribs of individuals at 5MT10010 and other sites in the Cowboy Wash area dating to various periods of occupation that had lesions on them suggestive of those seen in modern collections of individuals known to have died of tuberculosis and (to a lesser extent) other respiratory diseases. These lesions were found in 11 of 32 individuals from Cowboy Wash that had enough of their ribs left to examine. One of the individuals with lesions was from 5MT10010. This was an adult woman who was not one of the victims of the attack at site abandonment but who had instead died earlier and been formally buried. Lambert also examined comparative collections of remains from Pueblo Bonito at Chaco and Elden Pueblo near Flagstaff Arizona. Only 3 of the 45 individuals from Pueblo Bonito and 2 of the 20 from Eldon Pueblo had similar lesions, suggesting that this disease was much more prevalent at Cowboy Wash than at these other sites, even though it was not absent at them. Lambert notes that tuberculosis is an opportunistic disease that tends to strike people whose systems are compromised by other problems such as hunger and stress. The evidence for physical violence in the Cowboy Wash sample, even setting aside the cannibalism assemblages, was much greater than in the other two samples as well. Combined with the harsh environment, this suggests strongly that Cowboy Wash was a difficult place to live for several reasons. Farming was possible but risky, and when conditions turned bad both hunger and violence from other hungry people were constant threats.

Given this context, the occurrence of extreme events such as cannibalism incidents at Cowboy Wash starts to make some sense. Cowboy Wash is a place of extremes.

Huckleberry, G., & Billman, B. (1998). Floodwater Farming, Discontinuous Ephemeral Streams, and Puebloan Abandonment in Southwestern Colorado American Antiquity, 63 (4) DOI: 10.2307/2694110

Lambert, P. (2002). Rib lesions in a prehistoric Puebloan sample from southwestern Colorado American Journal of Physical Anthropology, 117 (4), 281-292 DOI: 10.1002/ajpa.10036

Read Full Post »